The Lee Street Massacre - Eighty Years of Silence

- Voodoo Flow Entertainment

- Jan 12, 2022

- 9 min read

Updated: Jan 13, 2022

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, it had to raise and train a huge army very quickly. A military draft began, and sixteen new army bases were established to train the soldiers. One was Camp Beauregard, Louisiana, located near Alexandria. It covered 60,000 acres, and approximately 45,000 soldiers received basic training there. It was one of the most modern military bases of its time. When World War I ended in November 1918, the army no longer needed Camp Beauregard, so it was closed the following year and the soldiers were sent home. The Camp was reopened in 1939 and in the Spring of 1940, military exercises recommenced, as the Army thought the mixed terrain east of the Sabine River would make for a good training area for foot soldiers and the warm weather meant they could be in the field longer and housed in rudimentary barracks. They were also happy with the landscape and climate conducive to expansive field exercises, so the Army soon began construction of three additional training facilities in the area - Camp Livingston, adjacent to Camp Beauregard; Camp Claiborne, located about 15 miles south of Alexandria; and Ft. Polk, approximately 45 miles west of town near Leesville. These camps formed a large complex of military bases in Central Louisiana as well as Camp Cook and Esler AirField.

The first soldiers arrived at Camp Livingston in early 1941, and by summer there were over 27,000 soldiers based on the campgrounds in approximately 900 buildings, with 7,850 residential tents. In mid-1941, the camp was the site of the Louisiana Maneuvers, a nearly half a million-man training exercise involving two imaginary countries fighting each other. The two armies faced each other across the Red River, over 3,400 square miles of land, including part of East Texas. The Red Army was made up of soldiers from Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, Missouri, and Kentucky and the Blue Army’s troops hailed from Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee. They were organized into a total of 19 divisions. This is still the largest maneuver in the U.S. Army’s history. Maj. Gen. George Patton, Lieut. Col. Omar Bradley, Col. Dwight Eisenhower, and a young 2nd Lieutenant named Henry Kissinger were among those on hand for the massive operations.

The 367th Negro Infantry Regiment, later renamed the 364th, was one of the earliest African American combat units and in March 1941, it was activated at Camp Claiborne. The Army wanted to keep close tabs on the regiment, so they placed white officers over them as their superiors. Instead of a peaceful transition the soldiers were subjected to demeaning and racist behavior and virtually treated as slaves. After several regiment members wrote letters to complain, their superiors intercepted the information and politely used it against them. Upon learning of the complaints, the Army intelligence began to label the 364th as "troublemakers". The situation grew worse after they were found to be advocates for the grass roots civil rights movement known as the Victory at Home and Victory Abroad (Double V) campaign.

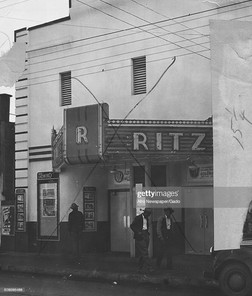

Throughout the war years, Camp Livingston, Camp Claiborne and Camp Beauregard were also home to several African American units hailing from northern states who were unversed in the Deep South Jim Crow laws. The heavy influx of troops brought economic rewards and prosperity to Alexandria. Lee Street was a thriving African American community in the 1940s. The area included restaurants, grocery stores, churches, entertainment venues, a sporting arena, an Army-YMCA-USA building, and the Ritz Theater, a vaudeville & movie theatre. It was a neighborhood comparable to Greenwood in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Lee Street was considered a popular destination for African American soldiers when they were on leave weekends from the area's military bases. The city’s public services and accommodations were heavily burdened when trying to deal with the numbers of soldiers pouring in.

Central Louisiana, in the Early/Mid-20th Century, was dominated by the logging and farming industries and it was the monetary foundation for most of its residents. Many farms were former plantations that continued to practice sharecropping. Some ex-plantation workers were also hired to work and build the new military camps and training facilities. The City of Alexandria was growing, and the Army was helping them do so. But the opportunities for African Americans were very limited although the businesses near Lee Street were thriving. White Southerners were against racial integration of the military which brought out more hostility towards the soldiers of color. In the wake of a wave of racial violence in 1941, Northern African American newspapers called for the removal of colored soldiers from Southern Camps stating, “Backed by the City’s Police, MP’s (Military Police) do not hesitate to beat up and kill Negroes in the street and in the jails.” It was no secret that racial indifference was the main act during this time. Army officials at Camp Claiborne, where about 8,500 Black troops were stationed, received several complaints from soldiers that MPs in Alexandria were “unnecessarily rough” with them. Military and civilian police officers were untrained to handle the influx—30,000 soldiers visited Alexandria on some weekends.

Following the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7th, 1941, the United States Army ordered Camp Livingston to be transformed to house enemy aliens and prisoners of war who were interned by the U.S. Justice Department. After being held in a quarantine station at Algiers, near New Orleans, Louisiana, these men would be sent on to Camp Livingston beginning later the next year. The internment facilities at Camp Livingston were designed to hold up to 5,000 German, Italian and Japanese aliens and POWs. Preparations for their arrival began in January of 1942. Tensions were high among the civilians and military personnel in and around Alexandria as well as across the country. War was imminent. The racial and socioeconomic divide continued to impact an already suffering community. It was considered to some … a powder keg.

The date was January 9th, 1942. Fridays were payday and the weekend celebrations had begun on Lee Street. That night, Joe Louis, the undisputed Heavyweight Boxing Champion, was defending his title against Buddy Baer at Madison Square Garden in New York City. The fight was an anticipated rematch between the two. Their first encounter ended with a TKO of Baer, so he was ready to take another shot at the champ. GIs were listening to reports all evening trying to find out who’d won. And, with four seconds left in the 1st Round, Louis KO’d Baer and the match was over. The outcome of the match reverberated throughout the country with heavy racial undertones. Many whites had high hopes that Baer would beat Louis this time. He had not. Yet, everyone seemed in good spirits, both black and white alike. The drinks were flowing. “Victory Girls” were looking for their new favorite soldier. Considering the circumstances, there were good vibrations in the air.

By Saturday afternoon, January 10th, Alexandria’s streets were bustling with a few thousand African American soldiers. Around 8pm that evening, an incident occurred in front of the Ritz Theater when, supposedly, a black soldier had stepped in front of a car driven by a white woman and then she called the police. The woman called for a local police officer who then immediately started to arrest him and other soldiers who had come out with him that night, stepped in. Hostilities rose when additional MPs were called in from Camp Livingston along with city and state police. Reports state that at least sixty Military Police, thirty city officers and state troopers and an undetermined number of white civilians engaged perhaps several thousand black troops along the four or five block corridors of Lee Street. Among the things they reported were that police were just shooting randomly into businesses. Additionally, many black civilians were caught up in the turmoil. A local paper reported that officers used thirty gas bombs on unarmed soldiers that night. The MP’s responding to the call were mainly from the 327th Military Police Escort Guard, while most of the African American troops involved were from the 367th Infantry Regiment and 785th Tank Battalion stationed at Camp Claiborne and the 350th Field Artillery Brigade quartered at Camp Livingston. The MPs came primarily from Wisconsin and Michigan; soldiers in the three black units hailed mostly from Pennsylvania, Illinois and New York.

Records are not clear on what exactly happened as official military records, newspaper coverage and stories told by survivors all reported different versions. The War Department’s official report indicates that three African American soldiers were critically wounded, and 29 others required medical treatment as a result of the ‘Riot.’ The Inspector General’s Office wrote in an internal report that year: “No fatalities resulted.” Captain Houston Greene, Commander of State Police Troop E, maintained that the state troopers involved in the riot did not fire a shot. Earlier, Alexandria Police Chief George Clay stated that the MPs had shot black soldiers. According to his version, city and state police had merely "fired into the air". Civilian witnesses, however, indicated that 20 to 300 soldiers were killed, others wounded, and numerous civilians were murdered or wounded, as well. Many say a riot occurred, but others actually say a massacre occurred in a battle that reportedly lasted between 2 and 6 hours claiming countless lives. It was clear that something indeed had happened. The police and the military cordoned off an eight-block area after the incident. Newspaper headlines read “No Deaths as Result of Saturday Night Clash Here Corps Says”, “28 Negro Soldiers Hurt in Riot” and “State Trooper Injured in Lee Street Riot”. One article spoke of “exaggerated reports” stating no one had been killed. The number of African Americans that were slain that night is unclear, but some accounts claim to be in the thousands. In an editorial response to the Army's press release, The Louisiana Weekly, reprimanded both the military and civilian police, stating the riot "gave them the opportunity they wanted, a slight excuse to shoot and beat Negro soldiers, as well as a chance to remind Negro civilians that this is still the South."

Healing the wounds of our past is necessary to progress in the future. Around 2000, an African American woman named Etta Compton started placing a wreath at the site of the Ritz Theater, which is now an empty lot. One of her relatives owned a business on Lee Street and found it important to memorialize the clash. Soon after, she asked a chapter of the Buffalo Soldiers Motorcycle Club, whose members are Black veterans, to take on the responsibility. New clues also emerged in 2000, when an unnamed Black mortician told a journalist that he’d been coerced by Alexandria police into embalming bodies and taking them to the local train station at night, suggesting they were then possibly shipped out of town. Death certificates were sent to relatives saying the men had died in training.

Years later, an anonymous letter appeared which indicated that a mass grave of victims of the Lee Street Massacre was at Holly Oak Cemetery, an African American cemetery established in 1923 in Pineville, a city across the Red River from Alexandria. Historians and many others believe a number of African American soldiers were killed that night and buried in a mass grave that’s now home to Holly Oak Cemetery. To uncover the truth, four nationally known researchers, including staff from the University of Mississippi, brought a ground penetrating radar device to the cemetery in October 2020. For several hours, the experts took photos using the device, flagging any spots of interest for future reference. In February 2021, the City of Alexandria erected a Historical Marker at 819 Lee Street, the former site of the Ritz Theater, recognizing the “Lee Street Riot of 1942”. As of December 2021, there have been no new reports on the progress at Holly Oak Cemetery. There have been obstacles behind legalities involved with attempting to exhume human remains. Only time will tell.

Unfortunately, not much has changed in and around Alexandria in the past 80 years. The racial and socioeconomic division continues. A large Confederate monument stands just outside the Parish courthouse. Confederate battle flags can be seen flying randomly off the side of the road. The ancestry of Central Louisiana has bred a culture that is more closed-minded now than before. People of color are still referred to by racial slurs in public settings. A sad fact about the Lee Street Massacre is that it changed the trajectory of so many families' lives. Businesses were destroyed and people were killed. Loved ones were told their soldiers were killed in a training exercise when in reality, they were murdered by their fellow servicemen, city and state police, and local civilians. Now, their bodies lay in an unmarked grave somewhere in rural Louisiana or beyond. Those men were proud to serve their country and it killed them because of the color of their skin. Nothing could ever repay their descendants for that. However, a formal apology from the government and an acknowledgement that the atrocity happened would be a great place to start. Accountability would be next. My trust is that the truth will find its way to the surface and all the families involved may find closure.

Resources:

1. Memorial Day and the Lee Street Massacre | by Matthew Teutsch

2. Simpson, W. M. (1994). A Tale Untold? The Alexandria, Louisiana, Lee Street Riot (January 10, 1942). Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, 35(2), 133–149

3. Atlas Obsucra - Were Black GIs Killed in a World War II–Era Race Riot?

4. Mystery of the 364th - Mystery of the 364th (jayepurplewolf.com)

5. Joe Louis vs Baer II - https://www.thefightcity.com/joe-louis-vs-buddy-baer/

6. Bayou Brief - The Beginning of Hell

Comments